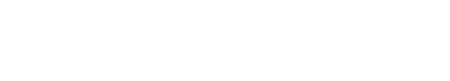

Aboriginal people weren't responsible for the noxious weeds that invaded Coomaditchie Lagoon and strangled the native plant life. But it was two Aboriginal sisters who took it into their own hands to clean up the mess.

The pair spends most of their days at Kemblawarra Community Hall, a studio gallery and home to the community group they founded in the early 1990s.

Subscribe now for unlimited access.

$0/

(min cost $0)

or signup to continue reading

But not so long ago, anyone looking for sisters Aunty Lorraine Brown and Aunty Narelle Thomas would have had a better chance of finding them down at Coomaditchie Lagoon.

Now 63, Lorraine's legs are too stiff to be walking around there like they used to - when she helped regenerate the whole area's bushland, the hard way.

"It's really heartbreaking because we can't get in there to do the things that we want to do, even just pottering around," she said.

Today they leave that to Steve Dillon and the crew from the Aboriginal land council's green team, but they live in hope that a younger generation will show an interest in the work they began in 1993.

Having just finished TAFE courses in youth and welfare work, and bush regeneration, Lorraine, 36, and Narelle, 26, were looking to put their skills to good use.

They set their sights on Coomaditichie, a significant Australian wetland, home to the eastern long-necked tortoise and green and golden bell frog, and a site that carried great significance for many Kemblawarra residents.

In the early 1940s the military took control of Hill 60 and surrounds, moving the Aboriginal community to a camp, before forcing them into a settlement at Coomaditchie.

"They said they'd give it back - they never ever got it back," Lorraine said of tribal lands at Port Kembla.

"They put them down in the sand hills near the lagoon, so we thought that was a significant area to regenerate and fix up."

The sisters pitched the recovery project to their bush regeneration teacher, Tina Bain, who threw her support behind the idea.

"Tina said 'Okay then', and then she said 'How about we try and get jobs out of it?''' Lorraine said.

"So we became incorporated and then we went for funding and we created 10 jobs out of that."

They established Coomaditchie United Aboriginal Corporation, which has been working to improve the wellbeing of Aboriginal people for more than 20 years. But in those early days, their focus was the lagoon - and they had their work cut out for them.

"It was pretty well neglected, as far as we were concerned," Lorraine said.

A section of the coastal dunes had been set aside as a receptacle for household waste, before becoming a steelworks dumping ground, with the mounds of coal wash edging closer and closer to the water.

Locals regularly used Coomaditchie as a shortcut, and had seen first-hand the damage caused by the tip.

"Some of the things had X's and skulls on some of the containers that went into the ground," Narelle said. "So that couldn't have been any good."

Then there were the weeds smothering almost everything in their path.

"It was totally bare (of native plants) when we did our studies," Lorraine said. "There were only a few remnants in the middle. So what we did was we completely stripped the hill."

They often wondered how much easier it would have been if they'd been allowed to practice cultural burning. As a girl, Lorraine would watch as her grandmother burned the bush at the top end of her property at Falls Creek in the Shoalhaven to protect them from bushfires.

"While she was doing it she was throwing witchitty grubs on the coals and she was having a feed of them. It was good times," Lorraine said. "Our people have done it for years."

"But there's laws here now," Narelle said. "You'd have to work with the fire brigade if you'd do that."

Without the burns, the work involved in reversing decades of environmental destruction was long and gruelling.

In their hands were big secateurs, loppers and pruning saws as they led a bush regeneration crew into dense shrubbery and tore it all down. They hacked into bitou bush as thick as trunks at their base; they climbed trees to remove the lantana that had scrambled its way to the top and covered it entirely.

"It was so thick we didn't even know there was an Old Man Banksia tree in there," Narelle said. "So when we come to that and the Port Jackson Fig we were really surprised."

At the end of each day, they walked home to Kemblawarra, aching and scratched all over. But they knew something special was taking shape as they painstakingly restored the spoiled land to its former glory.

"We used to get all the caterpillar dust on us, so we'd come out of there with lumps and bumps and scratches on our skin," Lorraine said.

"But it was worth it because every day we went there we could see the change that we were doing."

"When we cleared the bitou bush, as soon as we let light into those areas where it had covered, all the seeds it had dropped on the ground years before us had started coming up, even the ones we didn't want - weeds," Narelle said.

With the weeds finally cleared, it was time to mulch and replant thousands of native trees and to establish the bush tucker trail they'd envisioned from the start. Drawing on the traditional knowledge passed down by their elders and their recent TAFE studies, the team created a foodie's paradise.

"We had some ground covers, where we had midgen berries that taste like cinnamon, we had the lemon myrtle in there for the drinks, we had lomandra where you chew the base like a celery. We had the plum in there," Lorraine said.

"So we had a little rainforest area that was already there that was saved, it was the only little pocket of trees.

"So what we done was we put in our plums that are native to Wollongong - and we could tell the people that we had a soap tree there, to show how Aboriginal people used the leaves as a soap to wash themselves with.

"We also had trees out there where you could stun the fish, you know throw it in the water and stun 'em all. Bring them to the top so you could fish it out with nets."

They credit the lagoon's rebirth with boosting the self-esteem of their people and helping fight the racism they encountered from the broader community.

"It brought our community out and gave our community pride because they had ownership of that area," Lorraine said.

"We used to get stereotyped a lot. A lot of people didn't like Coomaditchie - they had their own ideas about the Aboriginal people who lived on here - so we've broken down a lot of barriers by opening the community centre."

Coomaditchie United Aboriginal Corporation - which expanded its services to include welfare support, art classes, cultural workshops and more - teamed up with Wollongong City Council and environmental groups over the years to maintain the lagoon and its surrounds.

But due to circumstances beyond their control, it's not what it was.

The fragile coastal habitat has been open to a host of threats, from stormwater runoff, to people lighting fires, to the dumping of commercial waste in the dunes.

"But the biggest damage for us was when somebody put carp in our lagoon," Lorraine said.

In early 2001, Coomaditichie was listed as an endangered ecological community under the NSW Threatened Species Act, due to the introduction of European carp.

"It meant death, practically," Lorraine said. "We've lost all the reed system from around this area. All the water hens could walk right across that lagoon on the reed system that was there. Gone.

"We used to have the baby turtles in our garden and we'd walk them back out cause they'd get in our soil and lay their eggs. You don't see it now. Years ago it used to be deafening here with frogs. You'd be very lucky to hear a frog now."

"You don't see hardly any swans there, only once in a blue moon with their cygnets," Narelle said. "They go down to the lake now but usually you see them swimming across and nest, they used to nest on there but not any more."

Work needs to be done to turn things around, but Lorraine and Narelle are grateful for the attention it does receive.

"It all needs picking up now but we need younger people to keep doing it," Lorraine said.

"Just to have Steve and the boys over there from the lands council, it's a real pleasure because we know our tracks get attention and it wasn't a waste of time.

"We appreciate all the volunteers who have put a lot of time and effort into this track - just ordinary bush-loving people. Thank you."

Find out more about the Coomaditchie United Aboriginal Corporation here.