While many in the Illawarra shunned those afflicted with AIDS, a rare few were caring for the sick and dying and helping to prevent the spread. More than 30 years later, they share their stories with the Mercury.

The early years

VIVIENNE CUNNINGHAM SMITH (COUNSELLOR): The Commonwealth Minister for Health Neal Blewett negotiated a bipartisan approach that would put health dollars into AIDS, so that's how the Port Kembla sexual health clinic got established. Dr Ross Price was the inaugural clinic director. I started work in February 1986 with my six-week-old baby in the pram, while Ross was teaching us about STDs and HIV. I had a lot to learn. My position as counsellor was accidentally advertised as full time and the clinic only ran for 12 hours a week so I had 20 odd hours a week that were purely focussed on education and prevention. We developed strategies to meet the needs of the medical and health community, the sex industry worker community, the gay community and the broader community. Needle Exchange programs were introduced in 1988 to address the issues in the injecting communities.

Subscribe now for unlimited access.

$0/

(min cost $0)

or signup to continue reading

DAVID WEBBER (ACON WORKER): The Illawarra branch of the Community Support Network (CSN) was established down here by a group of middle-aged heterosexual women. I get really emotional when I talk about it. What gets me is the fact that these women cared when they had no reason to - they just saw how poorly people were being treated. They provided care and support for people who were dying, a lot of the time without any family, working out of the boot of their car.

TRISH REGAL (CSN VOLUNTEER): It was the boot of my car actually. We were the 32nd group of volunteers to be trained by CSN, but the first in the Illawarra and the very first group made up of all straight women. The CSN trainers in Sydney were worried it we were do-gooders and people who wanted to save them and all that sort of rubbish. It was mostly all gay people in Wollongong at that point (with the virus). I think there was a couple who had blood products or something but they didn't need us because they had their families and it wasn't a social issue because they were the 'innocent victims' - and I detest that term, but that's how it was looked at. As CSN volunteers, we never went in and said 'this is what we will do'; it was more 'what would you like us to do for you?' It was a lot of cooking meals, just doing basic housework and shopping, and as they got sick we would be nursing them, so we might be changing dressings or beds, making sure they got things brought to them that they needed, often simply sitting with them, listening to them or just being there for them. We would do everything that needed to be done so they could die at home, if that's what they chose to do. Often after a client died, we would wash their bodies and contact whomever they had wanted us to call.

VIVIENNE: I was 26 when I started at the sexual health clinic. The first time I went to one of the brothels in Port Kembla, I was like 'Oh my god, what do I even say?' They were so gracious, they taught me the ropes of their work and allowed me to see where I fitted in. I used to go around and distribute free condoms as well as provide information to the women to protect their sexual health and for the reputable parlours this was not an issue. But the Port Kembla parlours were not consistently good, and generally the not-so-good ones were run by men. There was one that had really poor practice and he used to sell the free condoms to the girls but if a client didn't want to use the condom the girls were not allowed to insist they did. One young woman did insist and was beaten by the manager. These were challenging times.

Fear and paranoia

TRISH: We had to remain very, very anonymous. People with AIDS just weren't coming forward because they didn't want anyone to know what was wrong with them and even families thought they had leukaemia or a cancer of some sort. It was so hidden. One of the ladies in the CSN spoke to her manager who said yes we could use their premises in Wollongong to have meetings as long as it was after work and nobody who worked there was to know that the meetings were on. We used to literally hang around till everybody left the car park and then we would go in - talk about secret squirrel. If we saw another CSN volunteer in the street, we wouldn't even acknowledge each other. If either of us was with someone at the time and that person asked 'who was that', you may risk exposing, in a relatively small town, someone as being either involved with 'AIDS' or even themselves - many volunteers had not told their family or friends of their volunteering, such was the extent of the stigma at that time. You may also have been inadvertently disclosing a client whom you could be with at the time.

DR KATHERINE BROWN (SEXUAL HEALTH SPECIALIST): It was a very difficult time for patients and families. Some families welcomed their children home and looked after them if they were dying, some were not able to find it within themselves to be kind. There were families who would take their dying son home and wouldn't allow the son's partner, long-time partner sometimes, to visit or to be present at the funeral and that was terribly difficult for the people who suffered that rejection. And the health profession wasn't always helpful in the beginning.

VIVIENNE: In the very early days there were some health workers who were unsure and really didn't want to serve meals or go into the hospital rooms of people with HIV or AIDS. There was palpable fear about this disease and how you got it. The disease hit communities that were the 'other', it hit communities that were already excluded and health worker fear just reinforced the exclusion felt by gay men in those days. If someone was admitted, Ross used to talk to the doctors, the nurses; I'd educate the cleaners, kitchen staff and others involved in the person's care. There were no silly questions. Part of that dialogue was just about being honest and confronting what might have been the thoughts running through their head, acknowledging fear and not saying 'geez, you're a bad person because you've left the tray of food outside the door'. It was, 'Let's have a chat about how we can get the tray of food into that person's room because that's the dignified service the person in the bed deserves'.

Changing perceptions

VIVIENNE: I was a furious 'letter to the editor' writer in those very early days. Every time (then Illawarra Mercury editor) Peter Cullen published something on HIV actually. I was most irate at an article suggesting the tattooing of gay men's foreheads or bikini lines if they had HIV. We would have public stoushes about the views he was expressing in those early days, and then I thought, 'I can't continue to beat him up over his views, so I'm going to have to go in and work with this man because he's influential'. We had many long discussions. I started to get him involved in things and slowly it changed. By 1990 the messaging was very different and Peter became supportive of messages which promoted knowledge of HIV and challenged unhelpful attitudes. This was not a move to a community free of homophobia by any stretch of the imagination, but we didn't have these outrageously sensationalist headlines. There were always issues, though, that needed attention. I remember (then lord mayor) David Campbell calling me and going 'Viv, we've got a problem' - there were stacks of needles behind the Town Hall, and the media had gotten onto it. Dave always provided a steady hand, which was needed so we could get on with our work and not go down these extremely sensationalist avenues. I remember Shellharbour council was very different - they were talking about putting cameras in male toilets, known as beats, in those days.

DAVID CAMPBELL (LORD MAYOR): This was a new disease and people didn't know about it, they were scared of it, and there were people such as Vivienne trying to support people who had contracted the disease but trying to explain at the same time to the broader community what it was about. And it seemed to me as an elected representative at the time, let's just get some facts here and let's all just be calm and understand what's going on as best we can and support people who are sick. It was as simple as that really.

VIVIENNE: There were many events we held to spread knowledge about HIV and safe sex practices. Some of these were controversial. The AIDS TaskForce safe sex float in the Wollongong Festival in 1990 attracted Councillor Pat Franks' disapproval - she said it was anti-family and called for the float to be banned. This wasn't a great message so my four-year-old daughter, with her beautiful little pigtails, joined me on the float to make the point that HIV was indeed a family issue. Anyway, families didn't boycott it and we had a very respectful public dialogue that yes, HIV was a family issue.

Increase in services

VIVIENNE: After a few years, ACON - the AIDS council of NSW - opened an office in Wollongong so that really became a point where the gay community could mobilise and meet safely. As other groups and organisations became involved, we worked as one large team. ACON developed its role, the AIDS TaskForce developed its role, CSN had its role, and my role became more strategic as AIDS Co-ordinator, while the clinic always had its core role as being the centre of expertise. We had our differences at times, as every diverse team does, but everybody understood their different roles and what outcomes we were working for.

DAVID WEBBER: I came in at the end of the hysteria just as new medications and treatments were being developed. Part of my first lot of work as education officer with ACON was going to beats, public spaces where men have sex with men, so I was out talking to a whole range of different kind of men. Married men would take a long time to get to know and trust you, so the more word got around about who we were and what we did, the more they would feel at ease if we were to approach, chat and hand out condoms. Certainly a lot of men wouldn't talk to us at all because that environment is meant to be anonymous, discreet. You have to remember this was also a time when there were bashings and there was a lot of fear in the gay community around contracting, visibility discrimination and vilification. It was the gay community who came together to support people with HIV. We had a service down here called Our Pathways that was devoted to people living with HIV and I know the gay community, it didn't close ranks, but it certainly did a lot of activism and worked hard to make people's lives a bit better.

Towards understanding

VIVIENNE: The AIDS quilt was so important in those days. The AIDS TaskForce brought the quilt down every year and it wasn't the whole quilt, we were allowed parts of it, and that was just phenomenal. It was on display for several days, people could just come in quietly and each of the panels told a person's story. They were lovingly put together and utterly exquisite. It made a difference because it showed love, it showed respect. It showed individual lives that were impacted. The general public embraced it year in, and year out.

DAVID CAMPBELL: I can recall the AIDS quilt toured regional locations as an artwork really. And there were people who were saying we shouldn't have that hanging in the art gallery in Wollongong, for example, and when you look at it, it's significant for social reasons but also it's a significant piece of art, so for both reasons it was something that could and should be exhibited. I can remember arguing very strongly for the fact that this should come to Wollongong and hang somewhere prominently and be exhibited for those reasons. And it did eventually.

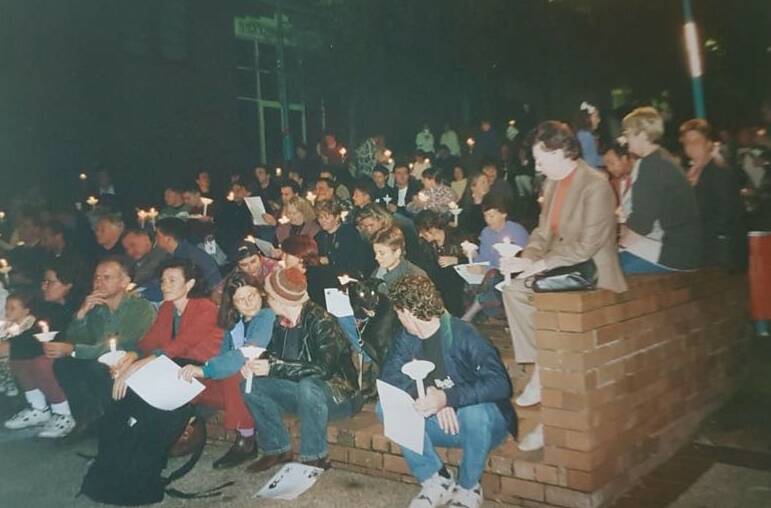

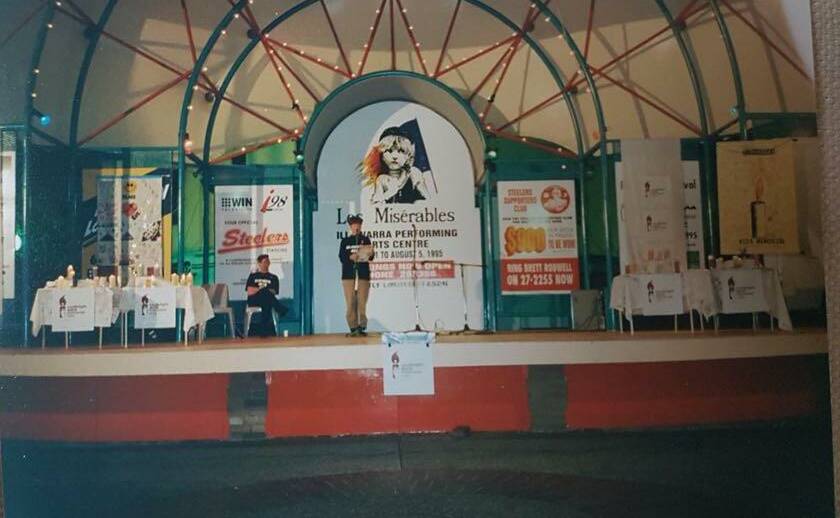

TRISH: We had world AIDS Day processions down Crown Street and services in the mall. We did a candlelight memorial in 94 and 95, so that was a few years in, but we were actually brave enough because the community wanted to and were ready to have a public memorial because people had been dying for a few years by then and nobody was really able to grieve openly. We got a lot of people come to that, it was quite surprising.

Better days, ongoing trauma

KATHERINE: When I first came to Wollongong, I still had a number of people die every year and a number of people with new infections, and we do still get infections but we rarely have people die. So it's no longer the case this is a very, very negative experience. Many of these people were very young. Most of us aren't used to talking to young people about dying - we don't really like talking to old people about dying, but it's even worse when you're telling a 20-year-old that this is something that is going to kill them. So to be able to move from a situation where every time you diagnosed someone with HIV, where your heart's in your mouth, where you had very little hope to offer people to now, where life expectancy is very similar to that of a person who doesn't have HIV ... it's still difficult because they're not usually expecting it, but it's just less difficult because you're able to say to people they will be okay. I saw a man the other day - I made his diagnosis about 15 or 20 years ago - and he said to me, 'You said to me when I was first diagnosed that I'd see you on your 70th birthday and here I am, I'm 70.'

DAVID WEBBER: I remember sitting on people's death beds and going through a whole range of different training in relation to that, to just this whole switch to well, how do people now plan to live longer on new medications? It happened over a couple of years, really massive improvements in treatment to the point now where we have combination therapy, pre-exposure, post-exposure prophylaxis - such a different environment to what I grew up in. It's a brilliant thing, don't get me wrong, but what we need to remember is that some people lived through a horrific period. My partner, who is six years older than me, doesn't have any social network left from that time. None at all. He would have been 30 when I met him, so just going through that in your 20s and losing lovers and friends in that environment where you're not treated as a human ... it had a really, really huge impact on people mentally.

TRISH: There's a couple I was very close to back then and still are because they're still here with us. A couple of long-term survivors, one I call my closest friend. There were a couple who devastated me when they went. I still have a bit of a weep when I think about them. It was very hard at times, but we had the most amazing support system. Somebody would die and we would all come together to debrief, celebrate and cry and laugh. Things are still not where they should be today, but boy I can not tell you how much it's changed since then. People are openly gay and it's just like whenever I hear anybody being open about their sexuality, I do a little happy dance inside. This is what I wanted. People are people, they're either nice people or not nice people. That's to do with their personalities, it's nothing to do with anything else.

We depend on subscription revenue to support our journalism. If you are able, please subscribe here. If you are already a subscriber, thank you for your support.