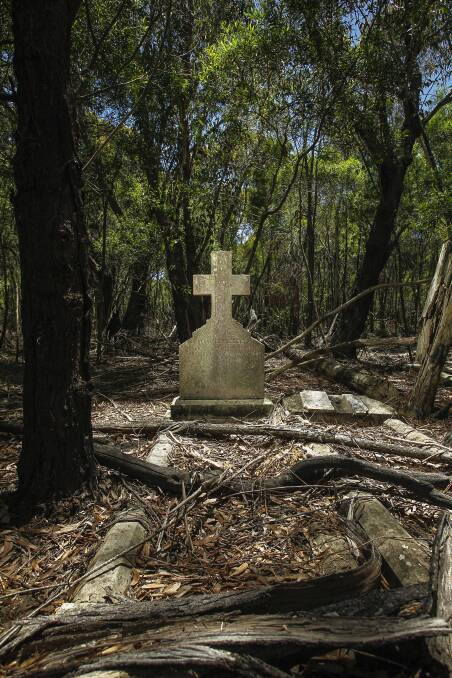

Nature has all but reclaimed the 2000 graves at Waterfall’s Garrawarra Cemetery after it was lost for more than 60 years. Kate McIlwain uncovers some of the haunting stories from the overgrown burial ground.

Subscribe now for unlimited access.

or signup to continue reading

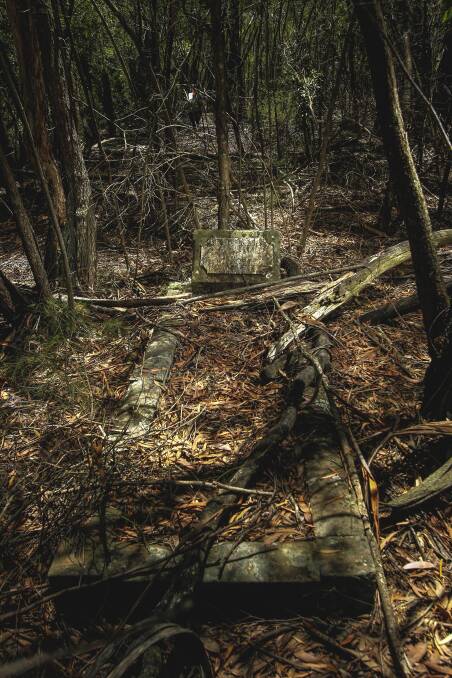

Garrawarra Cemetery is so covered by vines, broken branches and time, it's almost as though it never existed.

But beneath the dense bush that has grown over the graveyards lie the remains of 2000 souls, their stories forgotten for more than 60 years.

The cemetery, which also goes by the name of Waterfall General, was the final resting place for about half the tuberculosis patients who died at the nearby sanatorium early last century.

From 1909, when tuberculosis killed more Australian women than any other illness, the cemetery served as the state's only public facility for those with the deadly disease.

Society shunned tuberculosis patients and the stigma affected their families. Isolated in the bush and desperate for news of home, patients at Garrawarra would sometimes walk to the Waterfall rail line to wave at day trippers, who would toss them newspapers.

'At first, I thought there might be 50 or 60 graves in there; I had no idea there were thousands.'

There was faint hope of escape or survival. Clean mountain air and healthy food provided by the centre's orange orchards and dairy cows were little help once the disease took hold.

The sanatorium stayed open for about 10 years after the last grave was dug in 1949, but as vaccinations and antibiotics dramatically lowered infection rates, there was no longer need for public hospitals dedicated to tuberculosis.

In 1967, the records of the Waterfall General Hospital became lost in bureaucracy. The Wollongong City Council failed to take note of the cemetery records when the NSW Health Ministry offloaded general cemeteries in bulk to councils.

It was not until about two years ago that Wollongong City Council officially rediscovered Garrawarra while it was working on a project to rezone environmentally sensitive land.

Now, more than 60 years later, there's a push to rediscover the stories of those buried there.

With just rough directions and a mark on a map to guide me, I head west from Helensburgh to discover the lost cemetery for myself. It is not accessible to the public and, at first glance, the bushland that has covered the graves is indistinguishable from other patches of trees.

But then, as I step through the shadows, a lone intact gravestone rises out of the dried-out branches and eucalyptus leaves lining the forest floor.

A few steps later, another headstone emerges, and the hairs on the back of my neck prickle as I realise I'm probably standing on graves.

On the ground ahead, faint mounds showing where rows and rows of plots would have been are barely visible under the thick ground cover.

In some sections, charred wooden stakes line up, neatly spaced a few steps apart. They are the crumbling remains of the timber crosses that would have once marked some of the simpler graves.

Surprisingly, the ravages of time, falling branches and raging bushfires have spared some of the graves. There is no pattern to those that have survived, as headstones are dotted throughout the site at random. Of the 54 inscriptions still visible, no story is the same.

Vincent Arena died on February 4, 1926, aged just 16, a decade after 17-year-old Ada Alice Campbell was buried on New Year's Eve, 1916.

Frank Halladay lived to 58, before he was taken by tuberculosis on July 30, 1922, while Eileen Constance Grieves was 36 at the time of her death on May 18, 1936.

A sad irony is reflected in the dedications: in loving memory; never forgotten; remembered always.

Garrawarra Cemetery feels lonely. It's not unfathomable that you could get lost there and never be found.

Indeed, that's what might have happened to the graves if a series of events hadn't brought it to the attention of the council.

The rediscovery began in the late 1990s, when Illawarra historians Carol and John Herben began trying to gain access to the land and advise the council it was their responsibility.

The couple submitted a report in the early 2000s, but this was filed away for more than a decade.

Then, when councillors were deciding on the hotly debated rezoning of environmentally sensitive land in 2011, intrepid councillor Leigh Colacino noticed a mark on one of the maps that denoted a cemetery.

A Stanwell Park local who had never heard of its existence, Cr Colacino set off bushwalking with his wife, Jenny, to try to find the mysterious burial ground.

"We went in twice and missed the spot altogether, but then third time we managed to find it," he said.

"At first, I thought there might be 50 or 60 graves in there; I had no idea there were thousands."

From then, the cemetery was officially found.

The Herbens' report was uncovered and the council resolved to prepare a conservation plan to decide what should be done with the site.

In September, it launched a short film and asked the public what they would like to happen to the burial ground.

Mrs Herben has been heavily involved with efforts to track down family members and preserve Garrawarra's history.

"There's been some wonderful stories we've found," she said.

"In the gold-rush era, there was a man called Henry Beaufoy Merlin who took thousands and thousands of images of all the gold-rush sites. His son died in that sanatorium in 1927.

"Then you've got Cocker Tweedie, or Edward Tweedie - he wasn't buried there but taken from the sanatorium to Rookwood cemetery for burial - who was a champion boxer. They used to called them pugilists in those days.

"There's also a woman called Ellen Bruhn buried in the cemetery. Her brother-in-law, Norman Bruhn, was murdered in 1927 and he'd started the razor-gang wars in Sydney.

"There's people buried there from Scotland, France, Romania, Finland, Poland, Canada and Prussia because they either came straight off the ship or had nowhere else to go when they got sick just after they arrived in Australia.

"For that reason, I think this cemetery is of international significance."

Mrs Herben hopes this importance will make it eligible to be listed as a state or national heritage treasure.

Next month, councillors will consider various options for the cemetery's preservation, based on ideas put forward by the public last year.

While he'd hate to see it cleared and restored, Cr Colacino hopes there will be a way of making a pathway to the cemetery to allow relatives and other interested parties to visit.

"I think we need a way to let people experience the history there," he said.

"And we've got an obligation to the people buried there, who helped to build Australia in their own way."

Mrs Herben would like to see it left as is, but says family members could be invited to an annual service held by the council.

"All of them that's laying there, the 2000 of them, died a terrible death," she said.

"It's such a peaceful place that I think we should just leave the poor souls to rest there and leave it as a bush cemetery."

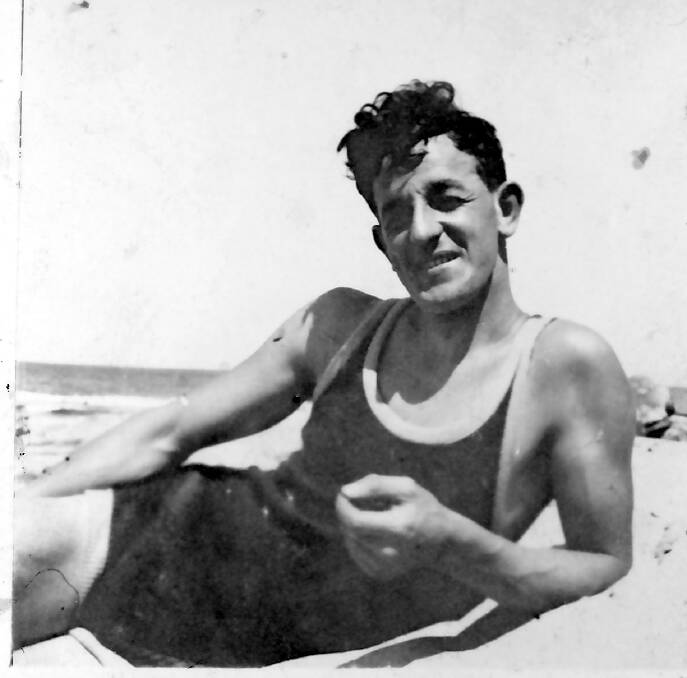

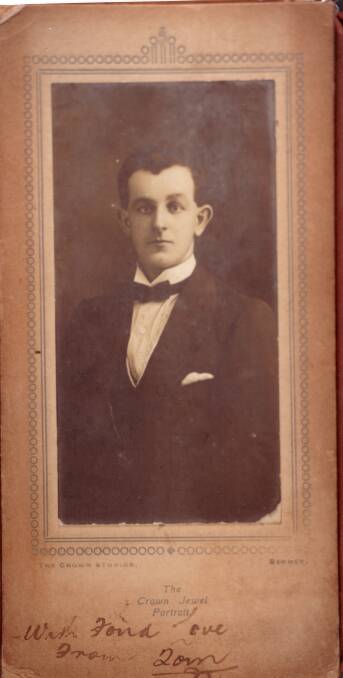

Sept 28, 1898 – Sept 15, 1923

Before the rediscovery of Garrawarra Cemetery, Penrith’s Sue Gorst always felt disconnected from her grandfather, Thomas Kennedy, thinking of him merely as her ‘‘mother’s father’’.

But finding his final resting place has allowed her to fill in the missing pieces of her family tree. Mr Kennedy married Lydia Best in 1921.

Their first daughter, Roma, Ms Gorst’s aunt, was born on February 8, 1922. Ms Gorst’s mother, Dell, was born at Parkes on May 15, 1923, but does not appear on Mr Kennedy’s death certificate, as he had been quarantined at a sanatorium. He died there four months later and was buried in the cemetery.

Ms Gorst’s mother began trying to find out about the father she never knew about 20 years ago. She applied for a copy of his death certificate, and found his place of death was listed as Waterfall Sanatorium.

The family searched in vain for his grave until, in November 2012, Ms Gorst read in the Sydney Morning Herald about the forgotten burial ground and watched ‘‘a missing page in our family history ... unfurl’’.

Sadly, her mother died in early 2012.

‘‘It’s been an amazing journey, which seems to have taken on a life of its own,’’ Ms Gorst said. ‘‘I had no emotional connection to my mother’s father at all, because my mum didn’t even know him.’’

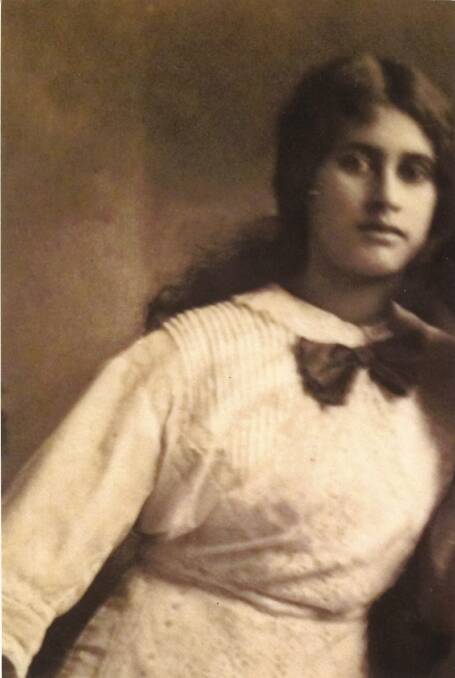

Feb 28, 1896 – Dec 24 1922 and Mar 16, 1898 – Dec 15, 1919

For Gold Coast resident Jody Faraone, finding out about her ancestors buried in Garrawarra Cemetery has opened a new chapter for her family.

Ms Faraone’s great-grandmother, Josephine Minister (nee French), died of tuberculosis at Garrawarra in 1922, aged 26, three years after her younger sister, Gertrude French, was buried at the cemetery.

Josephine left behind a four-year-old daughter, Mary Eileen French – Ms Faraone’s grandmother – who died several years ago without ever knowing how or where her mother died.

Ms Faraone tracked down the Frenchs in the northern NSW town of Casino and was told they were a respected local Aboriginal family.

‘‘I contacted the family and told them who we were. They knew that Josephine and Gertrude existed, but never knew what happened to them,’’ she said.

‘‘Knowing who our family was is really important, especially for my grandmother’s sake because she grew up not having any family. She always stressed to us that family was very important.’’

Ms Faraone said finding out about the sisters’ Aboriginal background shifted her perspective on ‘‘who we really are’’.

‘‘All my life, I’ve been asked what nationality I am, and I’d just say ‘I’m Australian, that’s all I know’.

‘‘Knowing we have Aboriginal heritage changes so many things – and explains a lot of things also. We’re proud of it, because it’s part of our history.’’

‘‘It’s really opened up my eyes to the ignorance in society, and in my life, about how we don’t really know about Aboriginal history or heritage.’’