As dawn breaks Sister Muriel Wakeford, in her crisp white veil and grey nurses’ uniform, stands ready on the deck of the hospital ship the Gascon, a pair of borrowed field glasses in her hands.

Subscribe now for unlimited access.

or signup to continue reading

The Wollongong woman watches as the Australian soldiers, all strong, athletic men, row in silence towards the narrow sandy beach at Gaba Tepe, later to be known as Anzac Cove.

The Gascon had arrived an hour before and was positioned 300metres from shore, but she did not drop anchor. Silence was paramount and all lights were out.

Muriel held up the binoculars in time to watch the first of the troops about to land and it was then she noticed that the narrow strip of beach was surrounded by ‘‘fearsomely high cliffs’’.

She was one of only eight women at Gallipoli on April 25, 1915. From their unique vantage point aboard the hospital ship, the seven Australian nurses and a matron, became eyewitnesses to a deadly and bloody history. No-one had expected the carnage that came so swiftly and easily for the Turks. Muriel watched in horror as bullets hailed down on the Anzacs, who dropped like flies on the sand. She saw the sea turn red with blood and corpses floating face down in the water. The beach too was littered with dead and wounded soldiers. The roar of machine-guns firing was deafening and sprays of bullets ricocheted off the water some narrowly missing the hospital ship, which Muriel said rocked violently from the falling shells.

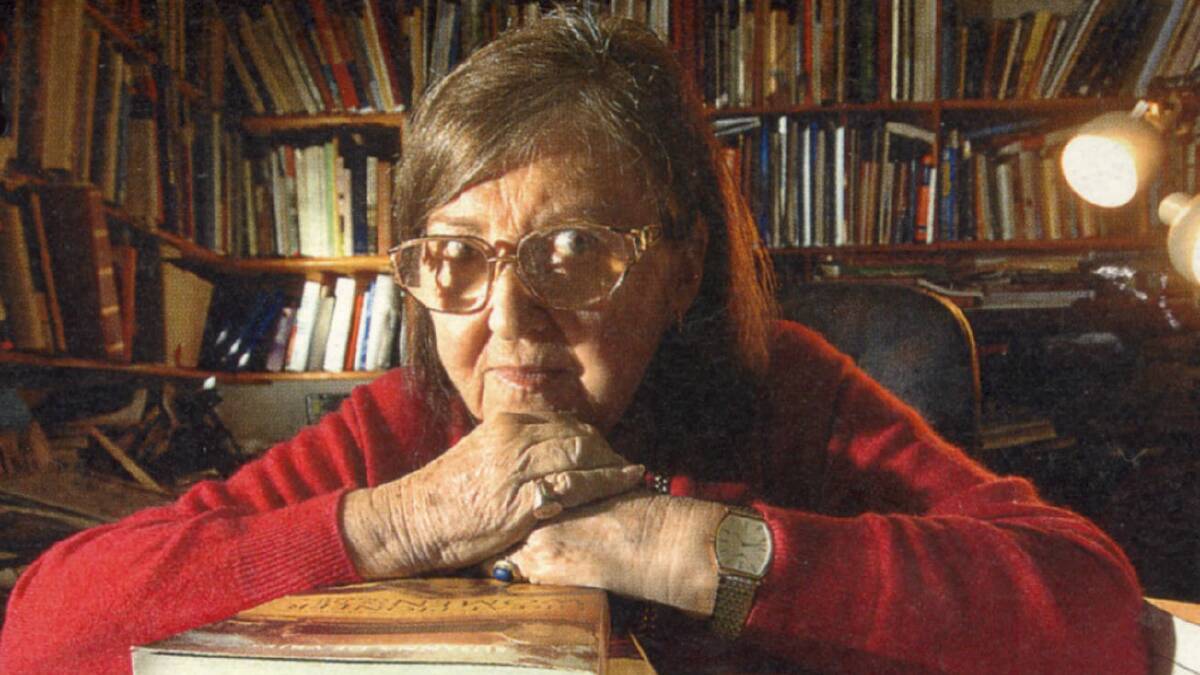

Nurse Wakeford is one of the heroines in Susanna de Vries’ (AM) new book, Australian Heroines of World War One, launched this week in Sydney.

‘‘Muriel was in a unique position because she was there that first Anzac Day,’’ says de Vries. ‘‘She sees the overview, she sees the men coming out of the boats, she sees them being picked off one by one, she sees them lying in the gullies. Later she becomes a whistleblower when the letters she sends home to her parents are published in the Illawarra Mercury.’’

A prolific writer, Muriel kept an account of that fateful day in her diary: ‘‘The wounded came down to the shore in an endless stream. Accommodation on the hospital ship soon gave out. After that occurred there seemed to be no one in charge directing wounded men to any one ship in particular. It was chaos on that beach. Soldiers, stores, mules and wounded men on stretchers struggled to find vacant space.’’

It was one of the biggest landing assaults ever attempted on an enemy shore – over the next few months 30,000Anzacs and 45,000soldiers from Britain and France set foot on the Gallipoli Peninsula. Their mission was to defeat the Turkish army and take Constantinople. The plan had been that the wounded would be treated at hospitals in Constantinople after the Allies had defeated the Turks. So sure of their success, there was only one hospital ship, the Gascon, a converted ocean liner, equipped to cope with just 400wounded.

In her diary Muriel recorded the following: ‘‘Our poor boys attempted to storm the high ground but many were wounded or killed by the guns of the Turks. Others rushed towards the cliffs to shelter from a hail of Turkish bullets. We could see wounded men lying in gullies and hoped stretcher bearers could reach them before they bled to death. Those men the stretcher bearers could not reach must have died a painful and lonely death.’’

At 9am the first of the wounded arrived on board the ship and Muriel set about tending to their wounds. Many had to have their limbs amputated by the ship’s doctor, or their eyes removed. By midday Muriel says Gallipoli was an inferno and the sky ‘‘grew dark with smoke’’.

By 4pm there were 560wounded men on board and at dusk the ship’s captain, concerned by the overcrowding, made the decision to head for Egypt, leaving behind hundreds of wounded soldiers on shore, with no pain killers, doctors or medicine. Many were moved onto the transport ships or ‘horse boats’, still covered in mule dung. A lack of clean bandages and antibiotics meant that their blood-soaked wounds quickly became infected and many men died before reaching Egypt. ‘‘It was scandalous,’’ Muriel later wrote in her diary. ‘‘That so many wounded men perished from infected wounds who might otherwise have been saved.’’

On board the hospital ship Muriel was a ‘‘front-line angel’’ to her patients and worked around the clock for the next two weeks, snatching a few hours sleep, often in an empty deckchair. Each day up to six men died on board and were buried at sea. It was heartbreaking work, but Muriel did her best, praying that the morphine wouldn’t run out and all the while spurred on by the ‘‘pluck’’ of the Australian soldiers. At 27, she had youth on her side and was much more capable of coping with the physical challenges of being a frontline nurse, than some of her older colleagues.

In one letter published in the Mercury by the-then editor Standish Musgrave, she sends out a plea for more medical staff to enlist.

"So many more doctors and nurses are wanted – I cannot understand why more do not come from Australia. Quite a number of men I know have been killed. I can quite imagine what a sad Australia it will be when the casualty lists come out. The roll of honour will be a very long one. People will begin to realise that this is war in earnest. The poor men in the trenches, living for a week at a time without sleep or a wash and very little food, and eventually getting these terrible wounds – it makes one wonder if it is worth the cost. The Australians are spoken of highly in every quarter. They are called the ‘die-hard Australians’ and I tell you they do die hard, too."

De Vries says she admires Muriel for allowing her letters to be published in the newspaper.

‘‘She braved censorship and she let the cat out of the bag as to how desperately they needed more doctors and nurses. The Mercury editor was brave too. At the time the newspapers were reporting that the Allies were winning an easy victory, they talked about how hopeless the Turks were and how everything was wonderful. Such letters were Australia’s first hint that things had not gone well at Gallipoli.’’

Muriel left Australia four days after enlisting in November 1914. The following April she was excited to have been assigned to the Gascon, a ship that would be treating Australian soldiers.

Before they boarded they were warned that fraternising with officers was forbidden. But among the chaos Muriel fell in love with Lieutenant Raymond Sergeant and the pair managed to keep their shipboard romance a secret.

Muriel didn’t dare write about her new love in her diary in case it was discovered. She was also forbidden to take photographs on board, but this rule she broke too, managing to take a few photographs of the man she loved. By September Muriel was rundown and was assigned to transport duty accompanying amputees back home to Melbourne. She told her Protestant parents that she was going to marry a Catholic man.

Muriel returned to Suez in December and married in London the following June. She resigned from her duties the day before her wedding, as at the time married nurses were forbidden to serve. She followed her new husband to Kenya where he took up a post as harbour master at Mombasa. Later in life they returned to London.

Muriel never saw her father again as he died of a heart attack in 1919. She returned to Australia in 1921 bringing her two-year-old son to meet her mother and the rest of her family. While there she petitioned Canberra for her war medals which were eventually forwarded to her.

Her nephew, Neil Wakeford said: ‘‘I met her in 1962 when she came out to Australia. The whole family went up to welcome her home as she got off ship. She encouraged me to travel and I was to stay with her in England in 1965, but she died a few months before I arrived. I met my wife while I was overseas so in a way she influenced my life; by encouraging me to see the world she set off a chain of events.’’

‘‘It must have been a big decision for Muriel to go to war in the first place, but she obviously felt a calling to do it,’’ he says.

‘‘I feel enormously proud of the work she did over there. She was so brave. It’s quite emotional really because I didn’t realise really what happened at Gallipoli until I read about it in her diaries. It was a tragedy.’’

In the eight months of fighting at Gallipoli 8141 Anzacs died and more than 18,000 Anzacs were wounded.

Excerpts of letters from Muriel Wakeford that were published in the Illawarra Mercury

21st January – We came by special train from Alexandria to Cairo, and I’m glad we shall have the opportunity to look after our own boys, when the expected fighting arrives, which must be before long. From my bedroom window I can see the Pyramids, in fact I could almost hit one with a stone.

7th April – The word has come at last. Orders are out tonight. I wonder where next you will hear of me, as we have not the slightest idea where we are going. But it is sure to be exciting. Your letter telling me not to climb the pyramids came too late, as I had already done so, it would never do to leave Egypt without doing that.

28th April – Just off duty. We have had a terrible time and no one but ourselves will know how we feel about everything that has happened. Rest assured, we have all done our very best. Two of us are doing night duty, Sister Burham and I. We do half the ship each, with a number of orderlies. The day staff come on very early and go off very late, and in that way get through a fair amount.

7th May – We have just returned with another 500patients, after being away one week. The fighting at ---- was terrific, and we were in the midst of it. So close that the shells from the enemy splintered a piece of the deck. The rifle fire is continuous and as soon as darkness sets in the flames were visible. I could scarcely have believed that we could be so close and feel absolutely no fear.

10 June – We were warned that our letters would be censored and that is why my letters are so vague. But I am going to chance something decent... At 1 am (April 25) we moved off. We reached Gaba Tepe around 4am. At 5am shells were bursting everywhere. At 9am our first lot of wounded came on board. At midday the place was a very inferno. The London was lying almost touching us, firing over our bows. Shells from the enemy frequently burst quite close to us. The first landing party were cut to pieces by the Turks, who fired shrapnel before the lighters even reached the beach. The majority of the wounds were in the left arms and the face, there were a number of spinal injuries, and fractured skulls and some very bad abdominal cases.