Filling out your family tree has never been easier than now, but, as GLEN HUMPHRIES discovers, keeping an eye on the future can help flesh out those family members perched on the branches.

Subscribe now for unlimited access.

or signup to continue reading

These days, the question "where did I come from?" is just as likely to be asked by an adult as it is by a child.

When it comes from a child, it's a question that stops with mum and dad (and probably prompts an awkward conversation).

The adult version of the question reaches back generations and centuries, and is asked more often now than ever before.

The proliferation and popularity of websites like ancestry.com.au have supported a surge in people wanting to piece together their family history.

According to a Time magazine report earlier this year, genealogy is so popular in the United States that it's the second-most visited category of websites (yes, porn is No 1). And there's really no reason to expect the results in Australia would be any different.

''I think somewhere deep down in us there’s this desire for connection, the desire to know who we are.''

But why has the quest to find out where you come from become such a popular one in the last decade?

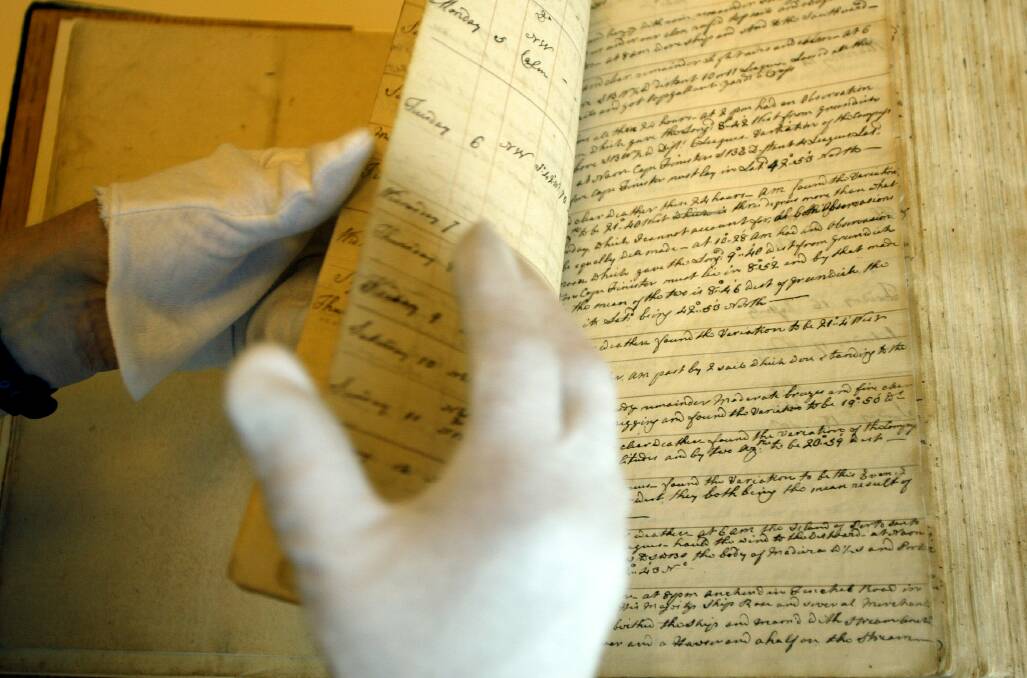

For some, the rise in interest is the result of technology. Being able to log into ancestry.com or one of a number of websites, typing in a few names and getting results is a lot easier than dedicating hours searching through hundreds of files looking for something with an ancestor's name on it.

And with so many people these days being time-poor, the internet delivers a better return on the time invested than shuffling through reams of paper. And, for some, searching through reams of paper requires more time invested than they can afford.

Others see the growing interest in filling out the branches of a family tree as fulfilling a deeper need for connection. With families spreading out, splitting up or sending their parents to a home, it's easier than ever before for people to begin to feel adrift.

That's when they start to look to the past to offer themselves some sort of anchor in the present.

For Rie Natalenko, the interest in genealogy is explained by this second factor, with people feeling disconnected from their own past.

"We've lost those connections with the past that we used to have," Natalenko says.

"Going back even 100 years, you'd had these extended families living together where the children would go into grandma's room and she would tell them the stories of her childhood.

"That doesn't happen any more. We put our old people into nursing homes and we lose that family connection.

"I think somewhere deep down in us there's this desire for connection, the desire to know who we are."

Natalenko is the creator of The Family Memory Project - a book aimed at helping people record the memories of ageing relatives while they're still around. She says it's all well and good to trawl through online archives, but people shouldn't forget about those repositories of family history still living.

"I want people to talk to their parents, talk to their grandparents," she says.

"I think a lot of people say 'oh I've done my family tree and I've taken it back to the 15th century'. Then when their mum passes on, they say 'I wish I'd talked to her when she was still alive. There are so many photos and I don't know who these people are or what their stories are.' Those are lost. You've lost those forever."

Her concept is a family history with an eye to the future. Though most people researching their history focus on the past, this is about looking to the future, to record things now so that generations down the line have more than just dates of births, marriages and deaths.

They have stories that really help to flesh out those people perched in the family tree.

She suggests asking your parents questions and recording or filming their responses.

She says putting on an "aura of fascination" at the beginning can help, but you can expect that fascination to become very real once they start talking.

Because, despite what you may think, your parents still have loads of stories they've never told.

One inventive approach Natalenko took with her own parents started with the Super 8 film footage they had shot over the years.

"We were going to lose [that] very soon because it's all going to deteriorate," Natalenko says.

"So I digitised the whole thing and then I sat down with my parents and they voiced over the whole lot.

"At 84 and 86, my parents did a voice-over of all their children growing up and where they were and 'do you remember'. It was one of the most emotional times of my life and now I've got that to give to my sisters and their children."

For those who do delve further back into their history, tracking down an ancestor who arrived on the First Fleet tends to be seen as the gold standard of genealogy in Australia - especially if they were a convict.

But that wasn't always the case, says Kerrie Christian, president of the South Coast chapter of the Fellowship of First Fleeters.

Christian, who has four First Fleeters in her tree - three of them convicts, says that for decades people never spoke of "the convict stain".

"I've seen articles dating back to about 1930 of my great-great-grandmother's obituary," Christian says.

"She was actually a descendant of three First Fleet convicts and a Third Fleet convict, but in the obituary she was described as being descended from a military officer on the Sirius, the flagship of the First Fleet.

"Even into the 1970s it was still considered a stain and it was only when the bicentenary came around that it changed. Now you find some people are disappointed if they can't locate a convict in their family tree."

The work on Christian's family tree began with her mother 30 years ago, who "did it the hard way" - which means "without the internet".

It was the family stories that got her mother started on her research.

"She looked after her mother and grandmother and I guess stories just got passed down," Christian says.

"My family has six generations buried at St Augustine's Anglican Church at Bulli and mum was the eldest daughter who lived closest so she was the one who went out there to put flowers on the graves at Christmas, Mother's Day and things like that. So she always had that connection."

It's continued with Christian, who set up family web pages that regularly uncover distant relatives. Several dozen of them are getting together in Wollongong this weekend, November 8-9, aligning with the 180th anniversary of the wedding of their ancestors: James Hicks and Margaret Daley.

Christian is also the president of the Illawarra Family History Group and says, surprisingly, the rise in interest in family research hasn't led to a surge in membership.

"I think what's happening is people are tending to think they can do it all via the internet, so you don't necessarily see an increase in numbers in the groups," she says.

"That's the challenge for all the family history groups. I think there is a benefit in participating in the groups because not all the records are on the internet. Some are in books or other record systems and you can get advice from other members on what records are where and how to interpret it."

The fascination with researching your past isn't anything new, Christian says. It's always been there, but now technology has made it feasible for people to start digging.

"I think there's always been an interest and the internet has just facilitated it," she says.

"For instance, nearly 13,000 people have joined [Facebook group] Lost Wollongong, from across the whole Illawarra. That tends to say to me there are an incredible number of people who are interested."

University of Wollongong senior lecturer in history and politics Glenn Mitchell says the internet and a desire to be connected are both driving factors in the rise of family researchers.

He also credits the influence of popular culture - for instance, the 1977 TV mini-series Roots, which inspired a lot of people in the United States to begin tracing their histories.

As well as uncovering your own past, Mitchell says the process can work to change people's perceptions of history.

"I think a lot of people studied history at school and for many of those people, history was a painful experience. Painful, boring, irrelevant," he says.

"What tracing your family tree does is allow you to be your own historian, in your own way, in your own time. I think it allows you to personalise the past. It allows you to put a stamp on at least one part of human history which is exactly yours.

"This allows people to see history come alive and allows them to place themselves in the grander scheme of things."

It can also inspire them to go further. If, say, someone found a relative who died during World War I, they might then move on to discover more about the battle.

Mitchell himself has delved into his own family tree and managed to uncover a surprise or two.

"When I looked at my mother's family tree and did some digging, I found it was larger than I ever thought because there were three children who had died very young - virtually after birth - that I'd never ever known about," he says.

"It's like any project where you start asking questions. Asking questions is a very, very powerful exercise and you don't know where it's going to go."