Dying and homeless – where do you go?

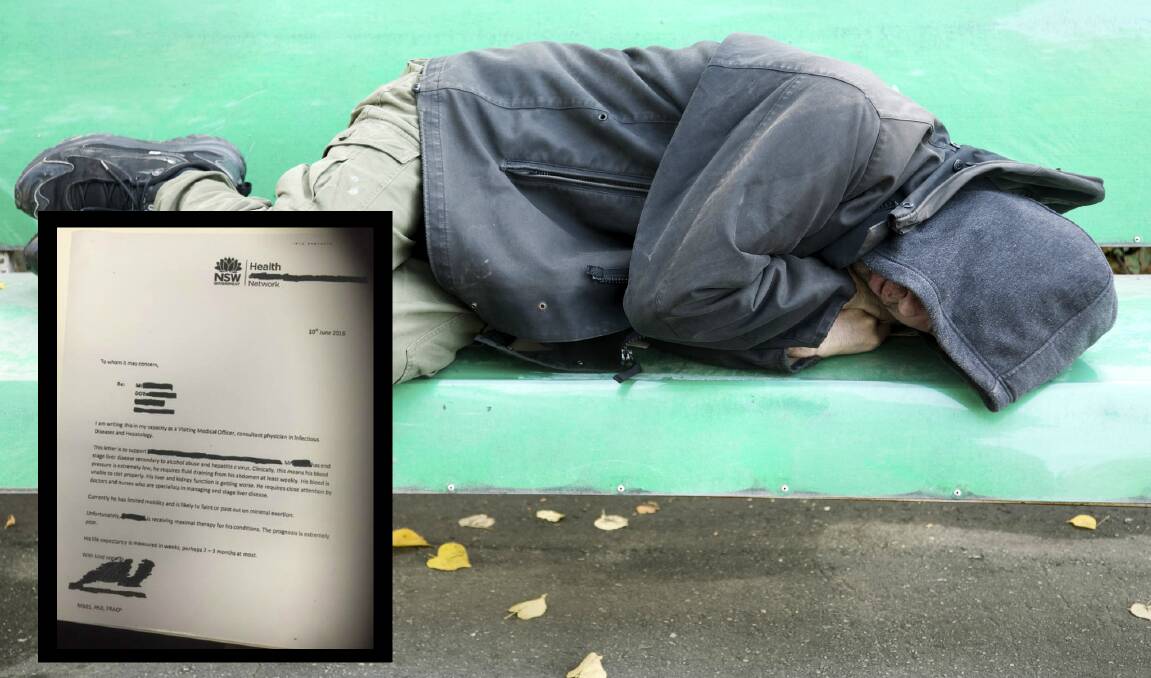

A month ago John (not his real name) was given three months – at most – to live.

Subscribe now for unlimited access.

or signup to continue reading

Suffering end stage liver disease due to alcohol abuse and hepatitis C, he has limited mobility, requires weekly fluid draining from his abdomen and such low blood pressure that a doctor advised in a letter that he was “likely to faint or pass out on minimal exertion’’.

The letter – dated June 10, 2016 – stated the 44-year-old’s life expectancy was “measured in weeks, perhaps two to three months at most’’.

“His liver and kidney function is getting worse. He requires close attention by doctors and nurses who are specialists in managing end stage liver disease,’’ it stated.

Yet on Monday, John was discharged from Wollongong Hospital; deemed ineligible for palliative care.

He’d heard of the Wollongong Homeless Hub, so walked two kilometres from the hospital to the Kenny Street service.

He told workers he was scared he’d have no crisis accommodation after discharge; he was afraid of “dying on the streets’’.

“At the end of the day, everyone has the right to die with dignity.’’

- Julie Mitchell

Unable to find emergency housing for him in the region, the Homeless Hub support worker took him back to the hospital. Staff there arranged an appointment with Housing NSW, before he was again discharged.

The Homeless Hub has kept in touch with John, and in the past week he has stayed at a hotel one night, been hospitalised again, and taken in for the night by a concerned resident.

After much wrangling, the hub has been able to work with Housing NSW to find John temporary accommodation.

‘’Unfortunately this is not an isolated incident, and it highlights the gaps in the system,’’ Hub manager Julie Mitchell said.

“At the end of the day, everyone has the right to die with dignity.’’

Dire need for men’s refuge

Wollongong Homeless Hub manager Julie Mitchell is calling on the Illawarra community to help fund a men’s refuge in the city.

Ms Mitchell said the hub has been offered a CBD premises rent-free for 12 months, yet needs funds to transform it into a 20-bed supervised facility.

The hub provides support services to the region’s homeless – a hot shower, a hearty breakfast, somewhere to clean clothes. It’s the link to other services which provide crisis accommodation.

However Ms Mitchell said too often the hub’s support workers could not find a place to stay for those who walked through the door, and could only offer them a bite to eat and a blanket for comfort as they were left to sleep on the streets.

The situation hit home this week with the case of a homeless man (see above) with liver disease who’s been given just weeks to live. Yet he was discharged from Wollongong hospital; deemed ineligible for palliative care.

The homeless hub could not source crisis accommodation for him, and now Ms Mitchell wants to take matters into her own hands so that men like him can have a warm bed, in a safe place.

There's a shortage of services; yet there shouldn't be a shortage of human kindness.

- Julie Mitchell

‘’There’s a shortage of services; yet there shouldn’t be a shortage of human kindness,’’ Ms Mitchell said. ‘’While there’s restrictions and limitations of what hospitals and other services can do, in an extreme case like this we can’t just harden our hearts and shrug our shoulders – we need to do more.’’

Census figures show that in the Illawarra around 1000 people are homeless each night. Refuges for women and children are struggling with demand. And the only men’s refuge – at Coniston – has been closed for several months for renovations.

‘’When we see a need, we rise to it. And that’s why we’re now looking into transforming this premises into a 20-bed refuge that is clean and well supervised,’’ Ms Mitchell said. ‘’So we can say to people in need, ‘yes, there’s a place for you to stay’.

‘’We are asking individuals, businesses and politicians in the region to support this; to support those falling through the gaps. These people can’t just be thrown on the rubbish heap of life.’’

Wollongong Hospital general manager Nicole Sheppard said staff worked closely with other local health and welfare services to support patients following discharge.

‘’This can be facilitated through nursing staff, social work and other patient support teams,’’ she said.

‘’Whilst we are unable to comment on individual cases, generally, a patient’s treating clinician works closely with our palliative care teams to assess whether or not admission to palliative care is an appropriate option.’’